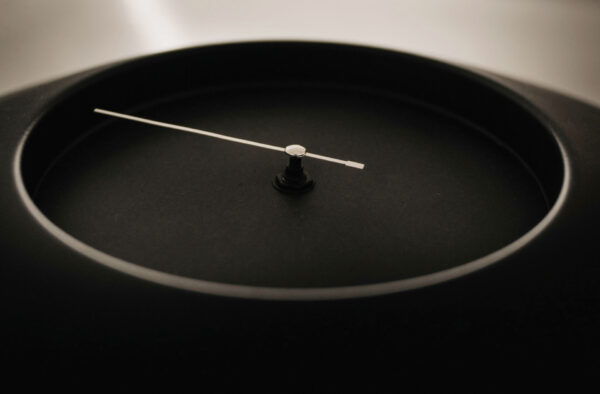

At the Same Time, 2020

engraved mirror, wooden frame

____________________________________________

Podroom Gallery – Cultural Centre of Belgrade, Republic Square 5/-1

Opening: March 16, 2022 at 19:00

16. 3 – 22. 4. 2023.

NELI RUŽIĆ

Timescape

Vremenski pejzaž

Curator: Irena Bekić

In collaboration with Art Pavillion in Zagreb and Cultural Centre of Belgrade

Additional programme:

Friday, 17 March

18.00 – Guidance through the exhibition with Neli Ružić and Irena Bekić

The exhibition by Neli Ružić titled Timescape, in Zagreb, at the facade of the Main Railway Station, Art Pavillion, Vranyczany Palace (Croatian Engineering Association) and Belgrade Podroom Gallery it represents a whole in which her last artpiece Timescape repeats and changes itself through time and spatial contexts of the two cities.

„… Neli starts from the idea that all timelines or a plurality of them are simultaneous, that we are touched by or immersed in many of them even though not all of them are fathomable or accessible to us at the same time. The temporal structure she presupposes is no longer vertical or horizontal. It is spatialised in multiple directions, building spatial and conceptual networks that include both in front and behind, above and across, now and before, sensations and relationships. Therefore, Neli’s works about time, always concern space. Whether she uses it as an artistic material, symbolic framework or product, it is always a constitutive part of her strategy. …” (excerpt from the text by Irena Bekić)

The exhibition has a catallogue published by Art Pavillion in Zagreb.

Breathing Together (Measuring the Cosmos) 2021/2023 multichannel video-sound in-stallation Director of photography: Darko Škrobonja Sound composition: Carole Chargueron

*

Neli Ružić (1966, Split) is a multimedia artist who examines the perception of time, historical narratives, the intersectionality of personal and collective memory. She graduated from the Painting Department of the Faculty of Applied Arts in Belgrade and holds a Master’s Degree from the Facultad de Artes, UAEM, Mexico. She stages regular solo shows and has participated in numerous group exhibitions, projects and festivals in Croatia and abroad. In the late 1990s she moved to Mexico where she taught at the ENPEG La Esmeralda Art School in Mexico City, from 2003 to 2012. She won the T-HTnagradamsu.hr 2nd Prize at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Zagreb (2016), and the ArtsLink Fellowship (1996). Her works are kept in the collections of the Museum of Fine Arts in Split, Mu- seum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Rijeka, Museum of Con- temporary Art in Zagreb, Marino Cettina Gallery in Umag, Canal Mediateca Caixa Forum in Barcelona. From 2013 to 2021, she has been teaching at the School of Fine Arts in Split where she was also the head of the School Gallery until 2018. She currently works as an Assistant Professor in the Painting Department of the Arts Academy, University of Split.

Now (Kairos), 2021, clock, electric motor, steel tube Photo: Darko Škrobonja

Time cartographies

Zorana Đaković Minniti in conversation with Neli Ružić

Dear Neli, first of all welcome back to Belgrade, the city where you studied at the Faculty of Applied Arts in the 1990s, and then left soon after graduation. In one of the Novosti interviews, you talked about a feeling of temporal delay of sorts, produced in you by frequent displacements (migrations), which were accentuated by every return. What does this delay mean in the case of your return to Belgrade, even though this return is short-lived and is related primarily to the preparation of your exhibition?

Dear Zorana, thank you. It is true that displacements produced in me a sort of temporal delay. I realised that leaving, or returning, is not only related to changing one’s place of residence, but that it changes one’s relationship with time. Almost proportionally, distance or impossibilities of frequent visits result in the subjective perception of time, phenomena similar to an ellipsis in films. Displacement somehow decentres what has previously seemed immovable, characteristic of belonging to a particular place. New subjectivities arise that were not inscribed either in the body or in the memory before leaving or returning, and were therefore, unimaginable.

A quarter of a century delay has taken place. Partly because of the war, partly because of my departure to Mexico, and it lasted until 2015 when I participated in the project From Diaspora to Diversity, curated by Mića Karić, at the Remont Gallery. When it comes to this return, the distance is somewhat diminished, to about eight years.

For me, this represents a return to a space of sensibility that I built during my studies with the people who were my Belgrade home. Many of them are no longer in Belgrade (Beta, Stela) and some of the are no longer with us (Saša Mikrob, Dunja or Milan). Belgrade, however, is also a wound site because of everything we experienced in the 1990s, and because of its current state. What has, among other things, built my world during my student days in Belgrade were brilliant lectures such as 20th Century Poetics by Ljuba Gligorijević at the Faculty of Fine Arts; reading Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita and Bachelard’s The Poetics of Space; then poetry, especially that of Branko Miljković, whose collections I always carried in my bag; Tarkovsky’s films at the Museum of Contemporary Art, the Student Centre, Academy Club, Ekaterina Velika, meeting Ješa Denegri… These are junctures, important moments and people that define: you know exactly where these conversations, people, encounters took place. They are focused, sharp, they stand out because they are important. Of course, every encounter with Belgrade is always and completely new.

The return is always a new experience, everything is in motion, everything changes, us and places, new encounters of rhythms. But maybe a part of me is still there…

What are the key theoretical/artistic references in relation to which you reflect on the role of time and different aspects of temporality?

Through my artistic practice so far, I have systematically been exploring time. In my previous works, I dealt with the convergence of the personal and collective memory, and oblivion, in relation to my own experience of displacement and distance, then with historical narratives and the representation of history, their subordination to affect and ideology, personal and political. History, recollection and memory are key currencies of political trade, especially in the Balkans. Memory is at the centre of the struggle over representation of reality, and oblivion is in fact an integral part of what we remember. It is this relationship that shapes reality. Memory is selective and inventive. After all, we always remember from the present; each new present moment models the past. The past changes the most, you ́re never safe with it, says one of the protagonists of the audio work Do We Have a Plan for Yesterday?.

It was important for me to read the theoretician Mieke Bal’s book Heterochrony in the Act: The Migratory Politics of Time, in which heterochrony is a political category of resistance, a zero time that suppresses the interval. The convergence of different times, a phenomenon she associates with the migratory experience, relies on the notion of heterochrony, which Michel Foucault mentions in 1967 in Of Other Spaces. Giorgio Agamben is also important for me, especially his text What Is the Contemporary?. The book that became essential for Timescape is Franco Bifo Berardi’s Breathing: Chaos and Poetry. For a long time, I have also been influenced by the work and writings of Robert Smithson, the relationship between time, the geological, entropy and displacement. The experimental film that I am showcasing at the Podroom Gallery alongside Timescape, and especially the eponymous artist book, are also a dialogue with Smithson. Nigdina / NOWhere is an intermedial work, that is, it consists of an experimental film completed in June 2018 and an artist book created after the film in 2019, in collaboration with Irena Bekić and the Prozori Gallery. In the film Nigdina / NOWhere, I explore the reshuffling of identity and the perception of time in relation to the fates and conditions of two sculptures at the Klis Fortress: the remnants of my sculpture Before the Dawn, which I use to measure the time of my own absence, and the empty space where Bogdan Bogdanović’s monument Guardian of Freedom once stood. The latter provides a historical framework, a view of the politics of memory and oblivion. The absurd situation of these two sculptures, one installed temporarily, forgotten then re-found, and the other installed permanently and then dismantled, opens up space for observing the paradox of time. The dialogue between these two sculptures is intertwined with Robert Smithson’s textual and visual quotes from his series Mirror Displacements, 1968-69. I explore the non-linear flow and complex space-time formations. The book is not a story about the film, its starting point is a broader investigation of the perception of time and it problematizes the notion of return in the post-transition context. In a poetic way, it intertwines personal archaeologies and historical situations of erased and invisible histories. From the personal space of discontinuity – cracks and overlaps in the subjective understanding of time – I am trying to activate the accumulations of time that I faced upon my return, to understand the time that has gone by here, which for me did not exist. Departures and returns are not only related to the change of place, but also the time that we do or do not witness. Svetlana Boym writes in her book Rites of Return: The key issue in the rites of return is a frequent confusion of time and place, of the time of individual life and the time of history.

To what extent is time a measurable resource that is open to manipulation, management and control?

Time and the very perception of time develops in relation to the systems in which we live. The minute hand was introduced with the invention of the pendulum clock, while the seconds hand was not in use until the 18th century, the time of the creation of industrial capital and the industrial revolution. The synchronisation of local times has primarily taken place for the purpose of functional railway traffic management. Today, atomic clocks measure our time more precisely. This new inner sense of time that has inhabited our bodies during industrialisation, and has, in the age of late digital capitalism, accelerated precipitously is completely antagonistic to the workings of the body. Today, we live a fast-paced existence and temporality. The tyranny of time in relation to the slower rhythms of nature and ourselves. I am interested in how the subjective perception of biological duration is formed within economic and ideological systems, for example, the differences in the perception of time in socialism or capitalism, frugality and the culture of repair in relation to the current consumer mentality.

Measuring based on calendars and clocks, but also the productivity imperative and the fixed schedules it prescribes, regulate the rhythms of our lives and endurance. Compressed time, the pressure of time that becomes almost tangible and viscous. As Peter Weibel precisely defines it: This time-commodity as a new form of desire that has pretensions to eternity gloats over time of the human body and its finitude. In the daily rhythm, there is a constant lack of time. Measured in terms of usability, productivity and competitiveness, it constantly eludes us. I believe that as a result of an interruption in the steady rhythm, that we experienced during the pandemic years – especially the experience of lockdown at an individual, but also collective level – we understand more clearly that the perception of the passage of time is conditioned by economy and technology, even ideology. In addition to these social conditions of time, I am also interested in the relationship between the time we live in and the trans-generational, historical time, the relationship between human and non-human, biotemporality in relation to geological time or scientific time, such as the shortest interval of time ever recorded, 247 zeptoseconds, the time required for a photon to cross a single molecule of hydrogen.

The first time I saw your works was in 2015 at the Institute for Contemporary Art in Zagreb as part of the Time Lapsus exhibition, where you showcased the work Strategies of Oblivion. The history of the family coat, dry cleaners and hundreds of fabric pills created after numerous washing cycles unexpectedly provided the audience with so much information and fertile ground for deeper analysis of not only your work, but also other social processes related to the time period of the coat’s existence. Are Time Lapsus and Timescape connected and if so, how?

Time Lapsus is the predecessor of Timescape, but it deals with the residue. Specifically, both are processual works that record time: intergenerational, historical or the time of one’s own life. Like some kind of time machine, they connect works from the 1990s with works produced in Mexico and those created after my return. In 1996, in the photo-ambient of the Galeb Dry Cleaners I articulated the trauma of war for the first time, of ethnic cleansing, the post-war situation and erasure of collective memory. Strategies of Oblivion were created when I transferred this photo-ambient, as well as my aunt Zdenka’s coat to Mexico, where this coat evoked the ravenous times of the European 20th century even more intensely. The times of austerity and torpor. Strategies of Oblivion (2004 – 2015) is a processual work consisting of a wool coat, 12 framed dry-cleaning invoices and photo documentation of the process in the form of three artist books as evidence of the imperceptible, but certain disappearance during numerous times the coat was dry cleaned. Timescape, in turn, deals more directly with the perception of time in contemporaneity, but also with the disappearance of the temporal foothold and uncertainty.

In terms of production, what we could describe as a new segment of the exhibition in Belgrade is the part that relates to the work It’s Too Late to Give Up. Specifically, in the already quite “contaminated” public space of Belgrade, which is teeming with commercial content and whose numerous edifices and buildings have lost their original functions, as is the case with the Main Railway Station at Savski Square, which was supposed to correspond with the façade of the Zagreb Main Train Station,where the aforementioned work was exhibited previously, we were forced to look for other ways of setting up this work in Belgrade circumstances.

The work It’s Too Late to Give Up was created for the space of the railway station. The Main Railway Station building at Savski Square no longer serves its original function and the entire context of that part of the city has changed. This is why my intervention at the Belgrade railway station is inscribed in another time, that is, on an archival image. In addition to the distorted perception of time, I am also interested in the tensions between utopia and entropy, the possible and what did not happen. I want to intervene in the past, in another time as if it had not even passed, as if everything could be different, but I also want to send a message of empowerment from a different past future to the present. Svetlana Boym distinguishes between restorative and reflective nostalgia. Restorative nostalgia implies burying oneself in an idealized past that never existed. Reflective nostalgia critically considers the possibilities of the past in relation to the present – sometimes with irony – and calls for reflection on the potential of nostalgia for the future, because nostalgia is not only related to the past. It models resistance in the future and creates an alternative present. In addition to the photograph displayed at the exhibition, postcards with a manipulated photo of the Belgrade railway station will be distributed at Savski Square, and its digital version on social networks.